Supported by

Many Changes in the Ryder Cup Over 25 Years, and the Americans Seek One More

ST.-QUENTIN-EN-YVELINES, France — The last time the United States won a Ryder Cup on the road, Davis Love III was a fresh-faced American rookie instead of a savvy two-time captain, and Ian Poulter, the future leader of the European team, was a teenage fan spending his nights in a tent.

It was 1993, when holding a Ryder Cup in Europe still meant holding it in Britain. But the event has broken free of its traditional moorings in earnest now, as this week’s landing in the Paris suburbs makes clear.

The Ryder Cup and France seem an odd marriage at first — and second — glance: The French would much rather watch soccer or play tennis than obsess over a three-day team golf competition. (And aren’t the British leaving the European Union soon, anyway?)

The Cup is here on the Continent in search of new audiences and sustained momentum, and it will be back in 2022, pitching its merchandise tents at the Marco Simone Golf and Country Club in Rome.

By then, the Americans hope their long wait for a victory on this side of the Atlantic will be history.

“It’s not anything I need to mention in the team room,” said Jim Furyk, the captain of the United States team. “There’s not like a big ‘25’ sitting in there anywhere. They are well aware of it, and they are well aware of how difficult it is to win in Europe, and that’s the battle we fight this week.”

Twenty-five years is a generation, even in a sport where second acts are part of the script. Not one of the 24 men who played in the 1993 matches at the Belfry near Sutton Coldfield, England, are in this week’s matches at Le Golf National, although Poulter, the fiery Englishman who camped out to watch them, is on the European team at 42.

Two of the 1993 stars died too young: Payne Stewart of the United States at 42 in a 1999 airplane accident and Seve Ballesteros of Spain at 54 from a brain tumor in 2011.

Their deaths make the 1993 matches seem more remote in the mind’s eye. It was the first of 10 Ryder Cups that I covered, and the differences with today are a reflection of societal change, commercial success and an ever-increasing sophistication of athlete maintenance.

Entering the course in 1993 was as simple as rocking up to the main gate at the Belfry and flashing a ticket. On Thursday, reaching Le Golf National from the commuter train station at Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines for the final practice round required two bag checks, a bus ride through a secure perimeter, a trip through a body scanner, a pat-down and then a 10-minute walk through a winding, fenced-in pathway after passing a phalanx of French forces holding assault rifles.

France, like so many places, has come to this the hard way.

But the atmosphere inside the perimeter has changed, too. There were 30,000 spectators a day at the 1993 Ryder Cup. There will be more than 50,000 a day here, including about 7,000 at the first tee, where an imposing temporary grandstand dominates the landscape of the rolling, open course.

There are bigger crowds and more screens, large and small. What has not changed, strangely enough, are some of the British touches. The power plugs in the portable press tent are still United Kingdom plugs that require adapters in France. Most of the concession stands — “Fish & Chips” and “Hog Roast” and “West Cornwall Pasty Co.” — are still catering to the Ryder Cup’s roots (and the thousands of British fans who have arrived in France).

But the more meaningful changes since the United States beat Europe, 15-13, in 1993 have come in the teams themselves.

“There were no entourages in ’93,” Tom Watson, who was the American captain, said in “The First Major,” a book by John Feinstein. “Guys brought their caddies and their wives, and that was pretty much it.”

Watson, who tried and failed for an encore as the captain in 2014, sounded wistful. But he became a champion in a different era. Now Ryder Cuppers bring swing coaches, personal trainers and agents, and they are also tended to by a corps of vice captains. In 1993, Watson had no such support group, only a so-called partial helper in Stan Thirsk, who was Watson’s mentor and former golf instructor.

This year, Furyk and the European captain, Thomas Bjorn, each have five assistant captains, many of whom, despite not competing, are here with their own caddies. Love, 54, is in an assistant’s role after serving as the captain in 2016, when the Americans won at Hazeltine National Golf Club in Minnesota.

The Ryder Cup’s modern success has been rooted in a strong rivalry, though not really Europe versus the United States, which is no classic sports rallying point. The rivalry has been the European Tour versus the more lucrative PGA Tour, based in the United States.

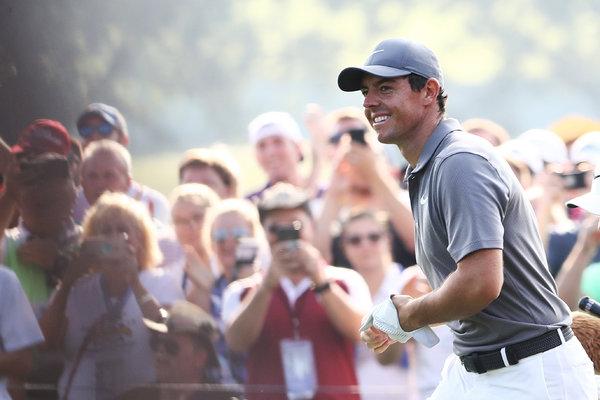

That lifestyle gap was a motor for the Europeans and made their dominance of the event in the 2000s all the more counterintuitive. But the lines between the teams have long since blurred, with Europe’s best routinely joining the American tour. In this globalized era, the Irish star Rory McIlroy knows the Americans’ games and characters better than he knows those of some of his European teammates.

In 1993, the Ryder Cup still felt like a genuine clash of golf cultures instead of a reshuffling of the deck. But that does not mean that ending the United States drought would fail to resonate, particularly for those who have lived it the longest.

Phil Mickelson, then fresh out of Arizona State University, was a candidate for a 1993 captain’s pick but was not chosen by Watson. His first Ryder Cup was in 1995, and he has not missed one since, going 0-5 on the road and losing in Spain, England, Ireland, Wales and Scotland.

Could France be where the streak stops?

“If we were to do that,” Mickelson said, “it would be something that I would remember and cherish for the rest of my life.”

On Golf

An occasional column looking at the news, issues and personalities of golf.

- Banksy Painting Self-Destructs After Fetching $1.4 Million at Sotheby’s

- Collins and Manchin Will Vote for Kavanaugh, Ensuring His Confirmation

- The Nazi Downstairs: A Jewish Woman’s Tale of Hiding in Her Home

- Trump Engaged in Suspect Tax Schemes as He Reaped Riches From His Father

- Opinion: The High Court Brought Low

- Susan Collins, Standing Alone, Makes Her Case for Kavanaugh

- Opinion: What It All Meant

- Opinion: An Insidious and Contagious American Presidency

- U.S. General Considered Nuclear Response in Vietnam War, Cables Show

- F.B.I. Review of Kavanaugh Was Limited From the Start

Advertisement

The article "On Golf: Many Changes in the Ryder Cup Over 25 Years, and the Americans Seek One More" was originally published on https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/27/sports/golf/ryder-cup-usa-europe-1993.html?partner=rss&emc=rss